Battleship Movie Download In Tamil Single Part

Posted By admin On 19.01.20.The Battle of Jutland (: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of ) was a fought between Britain's, under Admiral, and the 's, under Vice-Admiral, during the. The battle unfolded in extensive manoeuvring and three main engagements (the battlecruiser action, the fleet action and the night action), from 31 May to 1 June 1916, off the coast of Denmark's Peninsula. It was the largest naval battle and the only full-scale clash of in that war. Jutland was the third between steel battleships, following the long range gunnery duel at the and the decisive in 1905, during the. Jutland was the last major battle in world history fought primarily by battleships.Germany's High Seas Fleet intended to lure out, trap, and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, as the German naval force was insufficient to openly engage the entire British fleet.

- Battleship Movie Full For Free

- Battleship Movie Download In Tamil Single Part 2017

- Battleship Movie Download In Tamil Single Partner

This formed part of a larger strategy to break the British and to allow German naval vessels access to the Atlantic. Meanwhile, Great Britain's Royal Navy pursued a strategy of engaging and destroying the High Seas Fleet, thereby keeping German naval forces contained and away from Britain and her.The Germans planned to use Vice-Admiral 's fast scouting group of five modern to lure Vice-Admiral battlecruiser squadrons into the path of the main German fleet.

They stationed submarines in advance across the likely routes of the British ships. However, the British learned from signal intercepts that a major fleet operation was likely, so on 30 May Jellicoe sailed with the Grand Fleet to rendezvous with Beatty, passing over the locations of the German submarine while they were unprepared. The German plan had been delayed, causing further problems for their submarines, which had reached the limit of their endurance at sea.On the afternoon of 31 May, Beatty encountered Hipper's battlecruiser force long before the Germans had expected.

In a running battle, Hipper successfully drew the British into the path of the High Seas Fleet. By the time Beatty sighted the larger force and turned back towards the British main fleet, he had lost two battlecruisers from a force of six battlecruisers and four powerful battleships—though he had sped ahead of his battleships of earlier in the day, effectively losing them as an integral component for much of this opening action against the five ships commanded by Hipper. Beatty's withdrawal at the sight of the High Seas Fleet, which the British had not known were in the open sea, would reverse the course of the battle by drawing the German fleet in pursuit towards the British Grand Fleet. Between 18:30, when the sun was lowering on the western horizon, back-lighting the German forces, and nightfall at about 20:30, the two fleets—totalling 250 ships between them—directly engaged twice.Fourteen British and eleven German ships sank, with a total of 9,823 casualties. After sunset, and throughout the night, Jellicoe manoeuvred to cut the Germans off from their base, hoping to continue the battle the next morning, but under the cover of darkness Scheer broke through the British light forces forming the rearguard of the Grand Fleet and returned to port.Both sides claimed victory.

The British lost more ships and twice as many sailors but succeeded in containing the German fleet. The British press criticised the Grand Fleet's failure to force a decisive outcome, while Scheer's plan of destroying a substantial portion of the British fleet also failed. The British strategy of denying Germany access to both the United Kingdom and the Atlantic did succeed, which was the British long-term goal. The Germans' ' continued to pose a threat, requiring the British to keep their battleships concentrated in the North Sea, but the battle reinforced the German policy of avoiding all fleet-to-fleet contact. At the end of 1916, after further unsuccessful attempts to reduce the Royal Navy's numerical advantage, the German Navy accepted that its surface ships had been successfully contained, subsequently turning its efforts and resources to and the destruction of Allied and neutral shipping, which—along with the —by April 1917 triggered the.Subsequent reviews commissioned by the Royal Navy generated strong disagreement between supporters of Jellicoe and Beatty concerning the two admirals' performance in the battle.

Debate over their performance and the significance of the battle continues to this day. Contents.Background and planning German planning With 16 -type battleships, compared with the Royal Navy's 28, the German stood little chance of winning a head-to-head clash.

The Germans therefore adopted a. They would stage raids into the North Sea and bombard the English coast, with the aim of luring out small British squadrons and pickets, which could then be destroyed by superior forces or submarines.In January 1916, Admiral, commander of the German fleet, fell ill. He was replaced by Scheer, who believed that the fleet had been used too defensively, had better ships and men than the British, and ought to take the war to them. According to Scheer, the German should be:to damage the English fleet by offensive raids against the naval forces engaged in watching and blockading the, as well as by -laying on the British coast and attack, whenever possible. After an equality of strength had been realised as a result of these operations, and all our forces had been made ready and concentrated, an attempt was to be made with our fleet to seek battle under circumstances unfavourable to the enemy.

German fleet commanderOn 25 April 1916, a decision was made by the German admiralty to halt indiscriminate attacks by submarine on merchant shipping. This followed protests from neutral countries, notably the United States, that their nationals had been the victims of attacks.

Germany agreed that future attacks would only take place in accord with internationally agreed prize rules, which required an attacker to give a warning and allow the crews of vessels time to escape, and not to attack neutral vessels at all. Scheer believed that it would not be possible to continue attacks on these terms, which took away the advantage of secret approach by submarines and left them vulnerable to even relatively small guns on the target ships. Instead, he set about deploying the submarine fleet against military vessels.It was hoped that, following a successful German submarine attack, fast British escorts, such as, would be tied down by anti-submarine operations. If the Germans could catch the British in the expected locations, good prospects were thought to exist of at least partially redressing the balance of forces between the fleets. 'After the British sortied in response to the raiding attack force', the Royal Navy's centuries-old instincts for aggressive action could be exploited to draw its weakened units towards the main German fleet under Scheer. The hope was that Scheer would thus be able to ambush a section of the British fleet and destroy it. Submarine deployments A plan was devised to station submarines offshore from British naval bases, and then stage some action that would draw out the British ships to the waiting submarines.

The battlecruiser had been damaged in a previous engagement, but was due to be repaired by mid May, so an operation was scheduled for 17 May 1916. At the start of May, difficulties with condensers were discovered on ships of the third battleship squadron, so the operation was put back to 23 May. Ten submarines—, and —were given orders first to patrol in the central North Sea between 17 and 22 May, and then to take up waiting positions. U-43 and U-44 were stationed in the, which the Grand Fleet was likely to cross leaving, while the remainder proceeded to the, awaiting battlecruisers departing. Each boat had an allocated area, within which it could move around as necessary to avoid detection, but was instructed to keep within it. During the initial North Sea patrol the boats were instructed to sail only north–south so that any enemy who chanced to encounter one would believe it was departing or returning from operations on the west coast (which required them to pass around the north of Britain). Once at their final positions, the boats were under strict orders to avoid premature detection that might give away the operation.

It was arranged that a coded signal would be transmitted to alert the submarines exactly when the operation commenced: 'Take into account the enemy's forces may be putting to sea'.Additionally, UB-27 was sent out on 20 May with instructions to work its way into the Firth of Forth past. U-46 was ordered to patrol the coast of, which had been chosen for the diversionary attack, but because of engine problems it was unable to leave port and U-47 was diverted to this task. On 13 May, U-72 was sent to lay mines in the Firth of Forth; on the 23rd, U-74 departed to lay mines in the Moray Firth; and on the 24th, U-75 was dispatched similarly west of the Orkney Islands. UB-21 and UB-22 were sent to patrol the Humber, where (incorrect) reports had suggested the presence of British warships. U-22, U-46 and U-67 were positioned north of Terschelling to protect against intervention by British light forces stationed at Harwich.On 22 May 1916, it was discovered that Seydlitz was still not watertight after repairs and would not now be ready until the 29th. The ambush submarines were now on station and experiencing difficulties of their own: visibility near the coast was frequently poor due to fog, and sea conditions were either so calm the slightest ripple, as from the periscope, could give away their position, or so rough as to make it very hard to keep the vessel at a steady depth. The British had become aware of unusual submarine activity, and had begun counter patrols that forced the submarines out of position.

UB-27 passed Bell Rock on the night of 23 May on its way into the Firth of Forth as planned, but was halted by engine trouble. After repairs it continued to approach, following behind merchant vessels, and reached Largo Bay on 25 May. There the boat became entangled in nets that fouled one of the propellers, forcing it to abandon the operation and return home. U-74 was detected by four armed trawlers on 27 May and sunk 25 mi (22 nmi; 40 km) south-east of Peterhead. U-75 laid its mines off the Orkney Islands, which, although they played no part in the battle, were responsible later for sinking the cruiser carrying (head of the army) on a mission to Russia on 5 June. U-72 was forced to abandon its mission without laying any mines when an oil leak meant it was leaving a visible surface trail astern. Zeppelins.

The throat of the, the strategic gateway to the Baltic and North Atlantic, waters off Jutland, Norway and SwedenThe Germans maintained a fleet of that they used for aerial reconnaissance and occasional bombing raids. The planned raid on Sunderland intended to use Zeppelins to watch out for the British fleet approaching from the north, which might otherwise surprise the raiders.By 28 May, strong north-easterly winds meant that it would not be possible to send out the Zeppelins, so the raid again had to be postponed. The submarines could only stay on station until 1 June before their supplies would be exhausted and they had to return, so a decision had to be made quickly about the raid.It was decided to use an alternative plan, abandoning the attack on Sunderland but instead sending a patrol of battlecruisers to the, where it was likely they would encounter merchant ships carrying British cargo and British cruiser patrols.

It was felt this could be done without air support, because the action would now be much closer to Germany, relying instead on cruiser and torpedo boat patrols for reconnaissance.Orders for the alternative plan were issued on 28 May, although it was still hoped that last-minute improvements in the weather would allow the original plan to go ahead. The German fleet assembled in the and at and was instructed to raise steam and be ready for action from midnight on 28 May.By 14:00 on 30 May, the wind was still too strong and the final decision was made to use the alternative plan.

The coded signal '31 May G.G.2490' was transmitted to the ships of the fleet to inform them the Skagerrak attack would start on 31 May. The pre-arranged signal to the waiting submarines was transmitted throughout the day from the E-Dienst radio station at, and the U-boat tender Arcona anchored at. Only two of the waiting submarines, U-66 and U-32, received the order. British response Unfortunately for the German plan, the British had obtained a copy of the main German codebook from the light cruiser, which had been boarded by the after the ship ran aground in Russian in 1914. German naval radio communications could therefore often be quickly deciphered, and the British usually knew about German activities.The British Admiralty's maintained and interception of German naval signals. It had intercepted and decrypted a German signal on 28 May that provided 'ample evidence that the German fleet was stirring in the North Sea'. Further signals were intercepted, and although they were not decrypted it was clear that a major operation was likely.

At 11:00 on 30 May, Jellicoe was warned that the German fleet seemed prepared to sail the following morning. By 17:00, the Admiralty had intercepted the signal from Scheer, '31 May G.G.2490', making it clear something significant was imminent.Not knowing the Germans' objective, Jellicoe and his staff decided to position the fleet to head off any attempt by the Germans to enter the North Atlantic or the through the Skagerrak, by taking up a position off Norway where they could potentially cut off any German raid into the shipping lanes of the Atlantic or prevent the Germans from heading into the Baltic. A position further west was unnecessary, as that area of the could be patrolled by air using blimps and scouting aircraft. British fleet commanderConsequently, Admiral Jellicoe led the sixteen dreadnought battleships of the 1st and 4th Battle Squadrons of the Grand Fleet and three battlecruisers of the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron eastwards out of Scapa Flow at 22:30 on 30 May. He was to meet the 2nd Battle Squadron of eight dreadnought battleships commanded by Vice-Admiral coming from.

Hipper's raiding force did not leave the until 01:00 on 31 May, heading west of Heligoland Island following a cleared channel through the minefields, heading north at 16 (30 km/h; 18 mph). The main German fleet of sixteen dreadnought battleships of 1st and 3rd Battle Squadrons left the Jade at 02:30, being joined off Heligoland at 04:00 by the six pre-dreadnoughts of the 2nd Battle Squadron coming from the Elbe River.

Beatty's faster force of six ships of the 1st and 2nd Battlecruiser Squadrons plus the of four fast battleships left the Firth of Forth on the next day; Jellicoe intended to rendezvous with him 90 mi (78 nmi; 140 km) west of the mouth of the Skagerrak off the coast of Jutland and wait for the Germans to appear or for their intentions to become clear. The planned position would give him the widest range of responses to likely German moves. Naval tactics in 1916 The principle of was fundamental to the fleet tactics of this time (as in earlier periods). Tactical doctrine called for a fleet approaching battle to be in a compact formation of parallel columns, allowing relatively easy manoeuvring, and giving shortened sight lines within the formation, which simplified the passing of the signals necessary for command and control.A fleet formed in several short columns could change its heading faster than one formed in a single long column. Since most command signals were made with or between ships, the flagship was usually placed at the head of the centre column so that its signals might be more easily seen by the many ships of the formation. Wireless telegraphy was in use, though security (radio direction finding), encryption, and the limitation of the radio sets made their extensive use more problematic.

Command and control of such huge fleets remained difficult.Thus, it might take a very long time for a signal from the flagship to be relayed to the entire formation. It was usually necessary for a signal to be confirmed by each ship before it could be relayed to other ships, and an order for a fleet movement would have to be received and acknowledged by every ship before it could be executed.

In a large single-column formation, a signal could take 10 minutes or more to be passed from one end of the line to the other, whereas in a formation of parallel columns, visibility across the diagonals was often better (and always shorter) than in a single long column, and the diagonals gave signal 'redundancy', increasing the probability that a message would be quickly seen and correctly interpreted.However, before battle was joined the heavy units of the fleet would, if possible, deploy into a single column. To form the battle line in the correct orientation relative to the enemy, the commanding admiral had to know the enemy fleet's distance, bearing, heading, and speed. It was the task of the scouting forces, consisting primarily of and, to find the enemy and report this information in sufficient time, and, if possible, to deny the enemy's scouting forces the opportunity of obtaining the equivalent information.Ideally, the battle line would cross the intended path of the enemy column so that the maximum number of guns could be brought to bear, while the enemy could fire only with the forward guns of the leading ships, a manoeuvre known as '. Admiral, commander of the Japanese battleship fleet, had achieved this against Admiral 's Russian battleships in 1905 at the, with devastating results. Jellicoe achieved this twice in one hour against the High Seas Fleet at Jutland, but on both occasions, Scheer managed to turn away and disengage, thereby avoiding a decisive action.

Ship design Within the existing technological limits, a trade-off had to be made between the weight and size of guns, the weight of armour protecting the ship, and the maximum speed. Battleships sacrificed speed for armour and heavy naval guns (11 in (280 mm) or larger). British battlecruisers sacrificed weight of armour for greater speed, while their German counterparts were armed with lighter guns and heavier armour. These weight savings allowed them to escape danger or catch other ships. Generally, the larger guns mounted on British ships allowed an engagement at greater range. In theory, a lightly armoured ship could stay out of range of a slower opponent while still scoring hits. The fast pace of development in the pre-war years meant that every few years, a new generation of ships rendered its predecessors obsolete.

Thus, fairly young ships could still be obsolete compared to the newest ships, and fare badly in an engagement against them., responsible for reconstruction of the British fleet in the pre-war period, favoured large guns, oil fuel, and speed., responsible for the German fleet, favoured ship survivability and chose to sacrifice some gun size for improved armour. The German battlecruiser had equivalent in thickness—though not as comprehensive—to the British battleship, significantly better than on the British battlecruisers such as Tiger. German ships had better internal subdivision and had fewer doors and other weak points in their, but with the disadvantage that space for crew was greatly reduced.

As they were designed only for sorties in the North Sea they did not need to be as habitable as the British vessels and their crews could live in barracks ashore when in harbour. Order of battle. Main article:BritishGermanDreadnoughtbattleships2816Pre-dreadnoughts06Battlecruisers95Armoured cruisers80Light cruisers2611Destroyers7961Seaplane carrier10Warships of the period were armed with guns firing projectiles of varying weights, bearing warheads. The sum total of weight of all the projectiles fired by all the ship's broadside guns is referred to as 'weight of broadside'.

At Jutland, the total of the British ships' weight of broadside was 332,360 lb (150,760 kg), while the German fleet's total was 134,216 lb (60,879 kg). This does not take into consideration the ability of some ships and their crews to fire more or less rapidly than others, which would increase or decrease amount of fire that one combatant was able to bring to bear on their opponent for any length of time.Jellicoe's Grand Fleet was split into two sections. The dreadnought Battle Fleet, with which he sailed, formed the main force and was composed of 24 battleships and three battlecruisers. The battleships were formed into three squadrons of eight ships, further subdivided into divisions of four, each led by a. Accompanying them were eight (classified by the Royal Navy since 1913 as 'cruisers'), eight, four, 51 destroyers, and one. Commander of the British battlecruiser fleetThe Grand Fleet sailed without three of its battleships: in refit at Invergordon, dry-docked at Rosyth and in refit at Devonport.

The brand new was left behind; with only three weeks in service, her untrained crew was judged unready for battle.British was provided by the Battlecruiser Fleet under David Beatty: six battlecruisers, four fast, 14 light cruisers and 27 destroyers. Air scouting was provided by the attachment of the, one of the first in history to participate in a naval engagement.The German High Seas Fleet under Scheer was also split into a main force and a separate reconnaissance force. Scheer's main battle fleet was composed of 16 battleships and six battleships arranged in an identical manner to the British.

With them were six light cruisers and 31, (the latter being roughly equivalent to a British destroyer). Commander of the German battlecruiser squadronThe German scouting force, commanded by Franz Hipper, consisted of five battlecruisers, five light cruisers and 30 torpedo-boats. The Germans had no equivalent to Engadine and no to operate with the fleet but had the Imperial German Naval Airship Service's force of available to patrol the North Sea. All of the battleships and battlecruisers on both sides carried of various sizes, as did the lighter craft. The British battleships carried three or four underwater torpedo tubes. The battlecruisers carried from two to five.

All were either 18-inch or 21-inch diameter. The German battleships carried five or six underwater torpedo tubes in three sizes from 18 to 21 inch and the battlecruisers carried four or five tubes.

Battleship Movie Full For Free

The German battle fleet was hampered by the slow speed and relatively poor armament of the six pre-dreadnoughts of II Squadron, which limited maximum fleet speed to 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), compared to maximum British fleet speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). On the British side, the eight armoured cruisers were deficient in both speed and armour protection. Both of these obsolete squadrons were notably vulnerable to attacks by more modern enemy ships. Battlecruiser action The route of the British battlecruiser fleet took it through the patrol sector allocated to U-32. After receiving the order to commence the operation, the U-boat moved to a position 80 mi (70 nmi; 130 km) east of the Isle of May at dawn on 31 May. At 03:40, it sighted the cruisers and leaving the Forth at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). It launched one torpedo at the leading cruiser at a range of 1,000 yd (910 m), but its periscope jammed 'up', giving away the position of the submarine as it manoeuvred to fire a second.

The lead cruiser turned away to dodge the torpedo, while the second turned towards the submarine, attempting to ram. U-32, and on raising its periscope at 04:10 saw two battlecruisers (the 2nd Battlecruiser Squadron) heading south-east. They were too far away to attack, but von Spiegel reported the sighting of two battleships and two cruisers to Germany.U-66 was also supposed to be patrolling off the Firth of Forth but had been forced north to a position 60 mi (52 nmi; 97 km) off Peterhead by patrolling British vessels.

This now brought it into contact with the 2nd Battle Squadron, coming from the Moray Firth. At 05:00, it had to crash dive when the cruiser appeared from the mist heading toward it. It was followed by another cruiser, and eight battleships. U-66 got within 350 yd (320 m) of the battleships preparing to fire, but was forced to dive by an approaching destroyer and missed the opportunity.

At 06:35, it reported eight battleships and cruisers heading north.The courses reported by both submarines were incorrect, because they reflected one leg of a zigzag being used by British ships to avoid submarines. Taken with a wireless intercept of more ships leaving Scapa Flow earlier in the night, they created the impression in the German High Command that the British fleet, whatever it was doing, was split into separate sections moving apart, which was precisely as the Germans wished to meet it.Jellicoe's ships proceeded to their rendezvous undamaged and undiscovered. However, he was now misled by an Admiralty report advising that the German main battle fleet was still in port. The Director of Operations Division, Rear Admiral, had asked the intelligence division, Room 40, for the current location of German call sign DK, used by Admiral Scheer. They had replied that it was currently transmitting from Wilhelmshaven. It was known to the intelligence staff that Scheer deliberately used a different call sign when at sea, but no one asked for this information or explained the reason behind the query – to locate the German fleet.The German battlecruisers cleared the minefields surrounding the swept channel by 09:00.

They then proceeded north-west, passing 35 mi (30 nmi; 56 km) west of the lightship heading for the at the mouth of the Skagerrak. The High Seas Fleet followed some 50 mi (43 nmi; 80 km) behind. The battlecruisers were in line ahead, with the four cruisers of the II scouting group plus supporting torpedo boats ranged in an arc 8 mi (7.0 nmi; 13 km) ahead and to either side. The IX torpedo boat flotilla formed close support immediately surrounding the battlecruisers.

The High Seas Fleet similarly adopted a line-ahead formation, with close screening by torpedo boats to either side and a further screen of five cruisers surrounding the column 5–8 mi (4.3–7.0 nmi; 8.0–12.9 km) away. The wind had finally moderated so that Zeppelins could be used, and by 11:30 five had been sent out: L14 to the Skagerrak, L23 240 mi (210 nmi; 390 km) east of Noss Head in the Pentland Firth, L21 120 mi (100 nmi; 190 km) off Peterhead, L9 100 mi (87 nmi; 160 km) off Sunderland, and L16 80 mi (70 nmi; 130 km) east of Flamborough Head.

Visibility, however, was still bad, with clouds down to 1,000 ft (300 m). HMS Warspite and Malaya, seen from HMS Valiant at around 14:00 hrsBy around 14:00, Beatty's ships were proceeding eastward at roughly the same latitude as Hipper's squadron, which was heading north. Had the courses remained unchanged, Beatty would have passed between the two German fleets, 40 mi (35 nmi; 64 km) south of the battlecruisers and 20 mi (17 nmi; 32 km) north of the High Seas Fleet at around 16:30, possibly trapping his ships just as the German plan envisioned. His orders were to stop his scouting patrol when he reached a point 260 mi (230 nmi; 420 km) east of Britain and then turn north to meet Jellicoe, which he did at this time. Beatty's ships were divided into three columns, with the two battlecruiser squadrons leading in parallel lines 3 mi (2.6 nmi; 4.8 km) apart.

The 5th Battle Squadron was stationed 5 mi (4.3 nmi; 8.0 km) to the north-west, on the side furthest away from any expected enemy contact, while a screen of cruisers and destroyers was spread south-east of the battlecruisers. After the turn, the 5th Battle Squadron was now leading the British ships in the westernmost column, and Beatty's squadron was centre and rearmost, with the 2nd BCS to the west. (1) 18:00 Scouting forces rejoin their respective fleets.(2) 18:15 British fleet deploys into battle line(3) 18:30 German fleet under fire turns away(4) 19:00 German fleet turns back(5) 19:15 German fleet turns away for second time(6) 20:00(7) 21:00 Nightfall: Jellicoe assumes night cruising formationIn the meantime, Beatty and Evan-Thomas had resumed their engagement with Hipper's battlecruisers, this time with the visual conditions to their advantage. With several of his ships damaged, Hipper turned back toward Scheer at around 18:00, just as Beatty's flagship Lion was finally sighted from Jellicoe's flagship Iron Duke. Jellicoe twice demanded the latest position of the German battlefleet from Beatty, who could not see the German battleships and failed to respond to the question until 18:14. Meanwhile, Jellicoe received confused sighting reports of varying accuracy and limited usefulness from light cruisers and battleships on the starboard (southern) flank of his force.Jellicoe was in a worrying position. He needed to know the location of the German fleet to judge when and how to deploy his battleships from their cruising formation (six columns of four ships each) into a single battle line.

The deployment could be on either the westernmost or the easternmost column, and had to be carried out before the Germans arrived; but early deployment could mean losing any chance of a decisive encounter. Deploying to the west would bring his fleet closer to Scheer, gaining valuable time as dusk approached, but the Germans might arrive before the manoeuvre was complete.

Deploying to the east would take the force away from Scheer, but Jellicoe's ships might be able to cross the 'T', and visibility would strongly favour British gunnery – Scheer's forces would be silhouetted against the setting sun to the west, while the Grand Fleet would be indistinct against the dark skies to the north and east, and would be hidden by reflection of the low sunlight off intervening haze and smoke. Deployment would take twenty irreplaceable minutes, and the fleets were closing at full speed.

In one of the most critical and difficult tactical command decisions of the entire war, Jellicoe ordered deployment to the east at 18:15. Windy Corner Meanwhile, Hipper had rejoined Scheer, and the combined High Seas Fleet was heading north, directly toward Jellicoe. Scheer had no indication that Jellicoe was at sea, let alone that he was bearing down from the north-west, and was distracted by the intervention of Hood's ships to his north and east. Beatty's four surviving battlecruisers were now crossing the van of the British dreadnoughts to join Hood's three battlecruisers; at this time, Arbuthnot's flagship, the armoured cruiser, and her squadron-mate both charged across Beatty's bows, and Lion narrowly avoided a collision with Warrior. Nearby, numerous British light cruisers and destroyers on the south-western flank of the deploying battleships were also crossing each other's courses in attempts to reach their proper stations, often barely escaping collisions, and under fire from some of the approaching German ships.

This period of peril and heavy traffic attending the merger and deployment of the British forces later became known as 'Windy Corner'.Arbuthnot was attracted by the drifting hull of the crippled Wiesbaden. With Warrior, Defence closed in for the kill, only to blunder right into the gun sights of Hipper's and Scheer's oncoming capital ships. Defence was deluged by heavy-calibre gunfire from many German battleships, which detonated her magazines in a spectacular explosion viewed by most of the deploying Grand Fleet. She sank with all hands (903 officers and men). Warrior was also hit badly, but was spared destruction by a mishap to the nearby battleship Warspite. Warspite had her steering gear overheat and jam under heavy load at high speed as the 5th Battle Squadron made a turn to the north at 18:19. Steaming at top speed in wide circles, Warspite attracted the attention of German dreadnoughts and took 13 hits, inadvertently drawing fire away from the hapless Warrior.

Warspite was brought back under control and survived the onslaught, but was badly damaged, had to reduce speed, and withdrew northward; later (at 21:07), she was ordered back to port by Evan-Thomas. Warspite went on to a long and illustrious career, serving also in World War II.

Warrior, on the other hand, was abandoned and sank the next day after her crew was taken off at 08:25 on 1 June by Engadine, which towed the sinking armoured cruiser 100 mi (87 nmi; 160 km) during the night. Main article:At 21:00, Jellicoe, conscious of the Grand Fleet's deficiencies in night fighting, decided to try to avoid a major engagement until early dawn. He placed a screen of cruisers and destroyers 5 mi (4.3 nmi; 8.0 km) behind his battle fleet to patrol the rear as he headed south to guard Scheer's expected escape route. In reality, Scheer opted to cross Jellicoe's wake and escape via.

Luckily for Scheer, most of the light forces in Jellicoe's rearguard failed to report the seven separate encounters with the German fleet during the night; the very few radio reports that were sent to the British flagship were never received, possibly because the Germans were jamming British frequencies. Many of the destroyers failed to make the most of their opportunities to attack discovered ships, despite Jellicoe's expectations that the destroyer forces would, if necessary, be able to block the path of the German fleet.Jellicoe and his commanders did not understand that the furious gunfire and explosions to the north (seen and heard for hours by all the British battleships) indicated that the German heavy ships were breaking through the screen astern of the British fleet.

Instead, it was believed that the fighting was the result of night attacks by German destroyers. SMS Seydlitz was heavily damaged in the battle, hit by twenty-one main calibre shells, several secondary calibre and one torpedo. 98 men were killed and 55 injured.At Jutland, the Germans, with a 99-strong fleet, sank 115,000 long tons (117,000 t) of British ships, while a 151-strong British fleet sank 62,000 long tons (63,000 t) of German ships.

Battleship Movie Download In Tamil Single Part 2017

The British lost 6,094 seamen; the Germans 2,551. Several other ships were badly damaged, such as Lion and Seydlitz.As of the summer of 1916, the High Seas Fleet's strategy was to whittle away the numerical advantage of the Royal Navy by bringing its full strength to bear against isolated squadrons of enemy capital ships whilst declining to be drawn into a general fleet battle until it had achieved something resembling parity in heavy ships. In tactical terms, the High Seas Fleet had clearly inflicted significantly greater losses on the Grand Fleet than it had suffered itself at Jutland, and the Germans never had any intention of attempting to hold the site of the battle, so some historians support the German claim of victory at Jutland.However, Scheer seems to have quickly realised that further battles with a similar rate of attrition would exhaust the High Seas Fleet long before they reduced the Grand Fleet. Further, after the 19 August advance was nearly intercepted by the Grand Fleet, he no longer believed that it would be possible to trap a single squadron of Royal Navy warships without having the Grand Fleet intervene before he could return to port. Therefore, the High Seas Fleet abandoned its forays into the North Sea and turned its attention to the Baltic for most of 1917 whilst Scheer switched tactics against Britain to unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic.At a strategic level, the outcome has been the subject of a huge amount of literature with no clear consensus. The battle was widely viewed as indecisive in the immediate aftermath, and this view remains influential.Despite numerical superiority, the British had been disappointed in their hopes for a decisive battle comparable to and the objective of the influential strategic doctrines of. The High Seas Fleet survived as a.

Most of its losses were made good within a month – even Seydlitz, the most badly damaged ship to survive the battle, was repaired by October and officially back in service by November. However, the Germans had failed in their objective of destroying a substantial portion of the British Fleet, and no progress had been made towards the goal of allowing the High Seas Fleet to operate in the Atlantic Ocean.Subsequently, there has been considerable support for the view of Jutland as a strategic victory for the British.

While the British had not destroyed the German fleet and had lost more ships than their enemy, the Germans had retreated to harbour; at the end of the battle the British were in command of the area. Britain, reducing Germany's vital imports to 55%, affecting the ability of Germany to fight the war.The German fleet would only sortie into the North Sea thrice more, with a, one in October 1916 and another in April 1918. All three were unopposed by and quickly aborted as neither side was prepared to take the risks of mines and.Apart from these three abortive operations the High Seas Fleet – unwilling to risk another encounter with the British fleet – confined its activities to the Baltic Sea for the remainder of the war. Jellicoe issued an order prohibiting the Grand Fleet from steaming south of the line of Horns Reef owing to the threat of mines and U-boats. A German naval expert, writing publicly about Jutland in November 1918, commented, 'Our Fleet losses were severe. On 1 June 1916, it was clear to every thinking person that this battle must, and would be, the last one'.There is also significant support for viewing the battle as a German tactical victory, due to the much higher losses sustained by the British. The Germans declared a great victory immediately afterwards, while the British by contrast had only reported short and simple results.

Battleship Movie Download In Tamil Single Partner

In response to public outrage, the First Lord of the Admiralty asked to write a second report that was more positive and detailed.

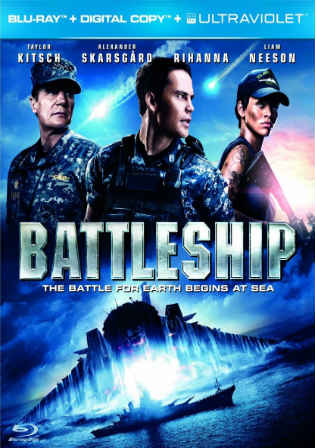

Frankly, I like this movie. It has balanced in story and actions, unlike the all actions but no story development in all three of the Transformers movies. Taylor Kitsch is more in character in this movie than he ever was in John Carter. Alexander Skarsgard is what a brother would be to his little brother and Rihanna is pretty damn good with her first acting gig. Overall, average actings from all the casts. The highlights of the movie is not the special effects but the 'tactical art of navy war' skills that the crews of the battleship is showcasing.

After watching this movie, I've learned that 'old things' are never meant to be forgotten.